As pills and gadgets proliferate, what matters is still social connection.

Source: What Technology Can’t Change About Happiness

In 2014, researchers at the University of Warwick in England announced they had found a strong association between a gene mutation identified with happiness and well-being. It’s called 5-HTTLPR and it affects the way our body metabolizes the neurotransmitter serotonin, which helps regulate our moods, sex drives, and appetites. The study asks why some nations, notably Denmark, consistently top “happiness indexes,” and wonders whether there may be a connection between a nation and the genetic makeup of its people. Sure enough, controlling for work status, religion, age, gender, and income, the researchers discovered those with Danish DNA had a distinct genetic advantage in well-being. In other words, the more Danish DNA one has, the more likely he or she will report being happy.

This tantalizing piece of research is not the only example of the power of feel-good genes. One body of research suggests we are genetically pre-programmed with a happiness “set point”—a place on the level of life satisfaction to which, in the absence of a fresh triumph or disappointment, our mood seems to return as surely as a homing pigeon to its base. As much as 50 percent of this set point, some researchers have demonstrated, is determined genetically at birth. The genetic determinants of a higher set point may be what the Danes are blessed with.

Neuroscientists are also studying a gene variant that leads to higher levels of a brain chemical called anandamide, which contributes to a sense of calm. Individuals with mutations that cause them to make less of an enzyme that metabolizes anandamide are less prone to trudge through life with the weight of the world on their shoulders. In 2015, Richard A. Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, lamented in a New York Times op-ed “that we are all walking around with a random and totally unfair assortment of genetic variants that make us more or less content, anxious, depressed or prone to use drugs.” “What we really need,” Friedman continued, “is a drug that can boost anandamide—our bliss molecule—for those who are genetically disadvantaged. Stay tuned.”

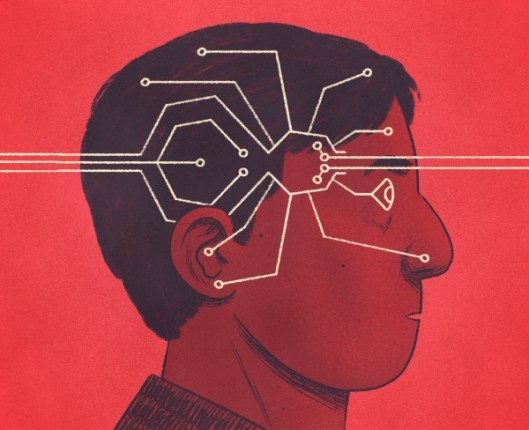

“Close relationships and social connections keep you happy and healthy. Basically, humans are wired for personal connections.”

Some scientists have already tuned in to the future. James J. Hughes, a sociologist, author, and futurist at Hartford’s Trinity College, envisions a day not too far from now when we will unravel the genetic determinants of key neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin, and be able to manipulate happiness genes—if not 5-HTTLPR then something like it—with precise nanoscale technologies that marry robotics and traditional pharmacology. These “mood bots,” once ingested, will travel directly to specific areas of the brain, flip on genes, and manually turn up or down our happiness set point, coloring the way we experience circumstances around us. “As nanotechnology becomes more precise, we’re going to be able to affect mood in increasingly precise ways in ordinary people,” says Hughes, who also serves as executive director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, and authored the 2004 book Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future.

It would be easy to conclude the redesigned human of the future will be able to pop a mood bot and live in bliss. But not so fast, say psychologists, sociologists, and neurologists who study happiness. Just because scientists have decoded some of the underlying biology of this ineffable state of being, paving the way for a drug to stimulate it, does not guarantee that our great-great-grandchildren will live happy and satisfying lives. Human nature is more than biology, the scientists assure us. And generations of happiness research offer a clear window into what it takes to live a long and satisfying life.

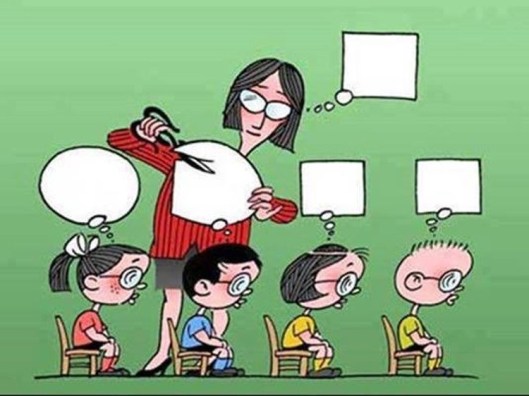

TOGETHER: Strong personal relationships lead to better health outcomes, and can shift the architecture of the brain. (Constance Bannister Corp / Getty)

The squishiness of the term “happiness” has long caused problems for those who study it. To gauge happiness and sidestep semantic problems, many of the psychologists who have tried to quantify it have used a measure called “Subjective Well-Being.” This measure, as its name implies, relies on individuals themselves to tell researchers how happy they are. Ed Diener, a University of Virginia psychologist nicknamed “Dr. Happiness,” pioneered the approach in the 1980s. Today, Diener serves as a senior scientist at The Gallup Organization, which provides a key survey used in happiness indexes put out by most groups compiling such lists, including the United Nations.

But in recent years, a growing number of researchers have begun to acknowledge that this isn’t a particularly good fix; maybe a little more refinement is needed. What we really mean when we tell a researcher from a place like Gallup that we are “happy” can vary widely. If you ask a teenager or young adult to rate his happiness, he’s liable to base his answer on his weekend plans, how much money he has in his pocket, and how his peers treated him during lunch break. If you ask somebody with a little more mileage—someone with children, for instance—they are liable to look at a bigger picture, even if they have a bad back that’s been acting up, no babysitter for Saturday, and an appointment that afternoon for a colonoscopy.

Over the past decade or so, a growing number of researchers have begun to rethink exactly what happiness is and distinguish between two types: “hedonic” happiness, that positive mental high, and “eudaimonic” happiness. Aristotle was referring to this second kind when he wrote 2,300 years ago: “Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.” This is the kind of happiness that qualifies a life well-lived, time on this planet well-spent. Medical technology may soon be able to engineer a momentary absence of fear, or the presence of a moment-to-moment sense of well-being, but engineering this second kind of happiness would be far more difficult.

Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard psychologist and author of the best-selling Stumbling On Happiness, suggests humans are already hardwired to raise their own hedonistic happiness, and we’re pretty good at it, without resorting to mood bots. Gilbert has spent his career studying the way we convince ourselves to accept our external circumstances, and return to a hedonic equilibrium, no matter what comes.

In a 2004 TED talk, Gilbert powerfully demonstrates this by displaying two pictures side by side. The picture on the left depicts a man in a black cowboy hat holding up an oversized lottery check. He has just won $314.9 million. The picture on the right displays another man, approximately the same age, sitting in a wheelchair, being pushed up a ramp. “Here are two different futures that I invite you to contemplate, and you can try to simulate them and tell me which one you think you might prefer,” Gilbert says to the audience. Data exists, he assures them, on how happy groups of lottery winners and paraplegics are. The fact is, a year after losing the use of their legs, and a year after winning the lotto, lottery winners are only slightly happier with their lives than paraplegics are.

The findings are unequivocal: Online connection decreases depression, reduces loneliness, and increases levels of perceived social support.

The reason people fail to appreciate that both groups are equally happy is a counterintuitive phenomenon that Gilbert calls “impact bias,” a tendency to overestimate the hedonic impact of future events. We see this tendency, he notes, with winning or not winning an election, gaining or losing a romantic partner, winning or not winning a promotion, passing or not passing a college exam. All these events “have far less impact, far less intensity, and for much less duration than people expect them to have.”

It’s that happiness set point again, returning to its base. But surely some things affect happiness? In fact, Gilbert tells Nautilus, “Much of our happiness is produced by things that have long evolutionary histories. I will place any wager that in 2045 people are still happy when they see their children prosper, when they taste chocolate, when they feel loved, secure, and well fed.”

These are the “staples of happiness,” he continues. “It would take an evolutionary change on the order of species to even consider the possibility that those would change too. This question could have been posed a few years ago, 300 years ago, 2,000 years ago. It would never have been wrong to say, ‘You are the most social animal on Earth, invest in your social relationships, it will be a form of happiness.’ ” It’s an answer that is so obvious that most people dismiss it.

“There is utterly no secret about the kind of things that make people happy,” Gilbert says. “But if you list them for people, they go, ‘Yeah, that kind of sounds like what my rabbi, grandmother, my philosopher have said all along. What’s the secret?’ The answer is there is no secret. They were right.”

erhaps the most compelling evidence on the importance of relationships stems from a study of a cohort of people who are today mostly grandparents themselves. The information is stored in a cramped room in downtown Boston, lined with file cabinets that hold the details of one of the most comprehensive longitudinal studies on the development of healthy, male adults ever compiled: the Harvard Study of Adult Development, previously known as the Grant Study in Social Adjustments.

In 1938, researchers began conducting tests and interviewing carefully selected college sophomores from the all-male Harvard classes of 1939, 1940, and 1941. The men were chosen not because they had problems that made them likely to fail, but because they showed promise. (The cohort included, among others, future president John F. Kennedy and Ben Bradlee, who would lead the Washington Post during Watergate.) The original intent was to follow these men, who seemed destined for success, for perhaps 15 to 20 years. Today, more than 75 years later, the study is still going. Thirty of the original 268 men in the study are still alive.

In 1967, the files were merged with the Glueck Study, a similar effort that included a second group of 456 poor, non-delinquent, white kids who grew up in Boston’s inner city in the early 1940s. Of those, about 80 are still around, though the ones that aren’t lived, on average, nine years less than those in the Harvard cohort.

In 2009, the study’s longest-serving former director George Vaillant was asked by Joshua Wolf Shenk of The Atlantic what he considered the most important finding of the Grant study since its inception. “The only thing that really matters in life are your relations to other people,” he responded.

After Shenk’s article came out, Vaillant found himself under attack from skeptics around the globe. In response, Vaillant created what he called the “Decathlon of Flourishing,” which included a list of 10 accomplishments in late life (60-80) that might be considered success. They included earning an income in the study’s top quartile, recognition in Who’s Who in America, low psychological distress, success and enjoyment in work, love, and play since age 65, good physical and mental health, social support other than wife and kids, a good marriage, and a close relationship with kids.

High scores in all of these categories turned out to be highly correlated with one another. But of all the factors he looked at, only four were highly correlated with success on all the measures, and those all had to do with relationships. Once again, he proved that it was the capacity for intimate relationships that predicted success in all aspects of the men’s lives.

“Mood bots,” once ingested, will travel directly to specific areas of the brain, flip on genes, and manually turn up or down happiness.

However, Vaillant, who detailed his findings in the 2012 book Triumphs of Experience, objects to the term “happiness.” “The most important thing in happiness is to get the word out of your vocabulary,” he says. “The point is that a great deal of happiness is simply hedonism and I feel OK today because I’ve just had a Big Mac or a good bowel movement. That has very little to do with a sense of well-being. The secret to well-being is experiencing positive emotions.” And the secret to that, Vaillant argues, might sound trite. But you can’t argue with the facts. The secret is love.

“In the 1960s and ’70s, I would have been laughed at,” to suggest such a thing, Vaillant says. “But here I was finding hard data to support the fact that your relationships are the most important single thing in your well-being. It’s been gratifying to find support for something as sentimental as love.”

Robert Waldinger, the psychiatrist and Harvard Medical School professor who currently leads the study, notes that it is not just measures of material success and psychological feelings of well-being that are linked to good relationships. It’s also physical health.

“The biggest take home from a lot of this, is that the quality of people’s relationships are way more important than what we thought they were—not just for emotional well-being but also for physical health,” he says. Marital happiness at age 50, he says, is a more important predictor of physical health at 80 than cholesterol levels at 50. “Close relationships and social connections keep you happy and healthy. That is the bottom line. People who were more concerned with achievement or less concerned with connection were less happy. Basically, humans are wired for personal connections.”

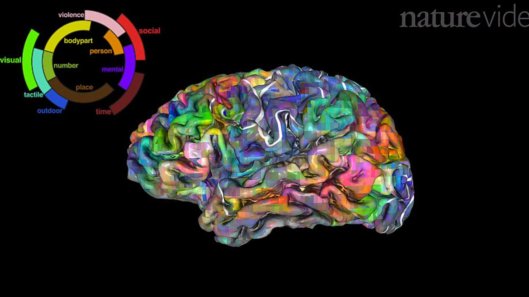

Not only did strong personal relationships lead to better health outcomes, it affected the architecture of the brain. People who feel socially isolated get sicker earlier, their brains decay earlier, their memories are worse, Waldinger says. Using brain-scan technologies, Waldinger and his team discovered that those who were most satisfied with their lives had greater brain connectivity. Their brains lit up more robustly when they looked at visual images than people who were less satisfied.

“The people who were most engaged were the happiest,” Waldinger says. “They could be raising kids, they could be planting a garden, they could be running a corporation. If you really care about something, if it means something to you, and particularly if you have meaningful engagement with other people when you do these things—those are the things that light you up.”

Even Nicholas Christakis, a Yale sociologist, who coauthored a seminal study of twins that demonstrated a 33 percent variation in life satisfaction could be attributed to the 5-HTTLPR gene, agrees that the key component to happiness is social. “I’m very skeptical that technological advances will affect what I regard as foundational features of human nature,” he says. “So I don’t think that any technological developments or futuristic things are going to fundamentally affect our capacity for happiness.”

Christakis, who studies social networks, says the influence of genes like 5-HTTLPR on happiness is less direct than a straight subjective feeling of well-being (though that may be part of it). Instead, he suggests, it’s their effect on our behavior that may be key—and the effect that has on our relationships. “It’s not just what genes do inside our body, how they modify our neurophysiology or transmitters, but what genes do outside our body, how they affect how many friends you make, or whether you will pick happy or sad friends, which also affects happiness,” Christakis says. “Even if you have genes that predispose you to pick happy friends, the unavailability of them may make you unhappy.”

DIGITAL BOND: Some scholars now argue that social media and the Internet draw people close together, enhancing already existing relationships. (Hero Images)

enerations of happiness research, stressing the importance of personal relationships, drops us into the middle of a surprisingly contemporary debate. We live in an increasingly networked society, and the rate of us in social networks, and the amount of time we spend online, continues to grow each year. Vaillant, of the longitudinal Harvard study, has no hesitation in saying what our lives online are doing to us.

“Technology drives us up into our cortex away from our heart,” he says. “What makes the world go round is not technology. It’s not having a better and better iPhone; I’ve got a fancy new phone and I just hate it. The technology is just going to distract us back into our heads so that my daughter feels it’s cooler to text someone than it is to talk to them on the telephone. That doesn’t bode well for happiness in 2050.”

The fears of a dystopian new world, where we all text at the dinner table and have problems making eye contact, were perhaps most articulately summed up by Sherry Turkle, professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology in the science, technology, and society program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She explores the paradox of how technology connects us, yet also makes us lonelier, in her 2011 book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other.

“Human relationships are rich and they’re messy and they’re demanding,” she argues passionately in a 2012 TED talk. “And we clean them up with technology. And when we do, one of the things that can happen is that we sacrifice conversation for mere connection. We short-change ourselves. And over time, we seem to forget this, or we seem to stop caring.”

Some of the earliest studies on the use of the Internet and technology supported the idea that the networked age was driving us toward a sad, lonely future. In a groundbreaking 1998 study, Robert E. Kraut, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, recruited volunteer families with high-school-aged children, gave them computers and Internet access, and then tracked their usage. The more his participants used the Internet, he found, the more their depression increased, and the more social support and other measures of psychological well-being declined.

Since then there have been other negative studies and a spate of bad press. One widely cited 2012 study conducted by researchers at Utah Valley University of 425 undergraduates found that the more they used Facebook, the more they felt that others were happier and had better lives than they did. The researchers named the study, “They Are Happier and Having Better Lives Than I Am: The Impact of Using Facebook on Perceptions of Others’ Lives.”

Even the Vatican has expressed concern. In 2011, Pope Benedict XVI warned in one of his messages to the world that “virtual contact cannot and must not take the place of direct human contact.”

But in recent years, a more nuanced consensus has begun to emerge—a consensus that suggests technology is not such a bad thing for human relationships. Carnegie Mellon’s Kraut now argues that his 1998 study might tell us about the present. The problem, he says, was there were comparatively fewer people on the Internet at the time. The individuals who participated in his study were forced to communicate with people they did not know in far-flung places, what Kraut calls “weak ties.” “What we realized is that by necessity they had to talk to relative strangers,” he says. “But that was the early days. Now virtually everybody you know is online.”

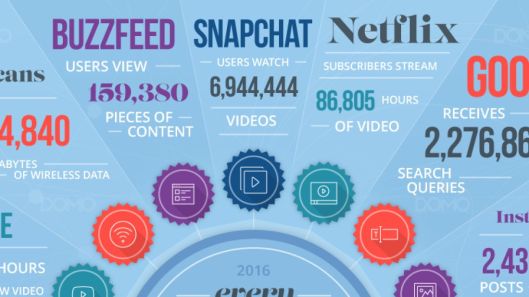

Kraut’s more recent research has found that today most people spend their time online communicating with people with whom they already have strong ties. In those cases, he argues, the findings are unequivocal: Online connection decreases depression, reduces loneliness, and increases levels of perceived social support.

It does so by enhancing offline relationships. Online interactions, like offline ones, are more fulfilling if they are with people with whom we have strong ties. They mean a lot less if they are with strangers. But most of us use technologies to communicate with people we already know. And that helps relationships grow stronger. “Communication online has the same beneficial effects that communication offline would have if we already know people,” Kraut says.

Keith Hampton, an associate professor of communication and public policy communication at Rutgers University, has conducted a number of studies in collaboration with the Pew Research Center measuring the effects of Internet use on relationships, democracy, and social supports. The idea that we interact either online or offline, he argues, is a false dichotomy. Through his studies, he too has become convinced that social media and the Internet are drawing us closer together—online and off. “I don’t think it’s people moving online, I think it’s people adding the digital mode of communication to already existing relationships,” he says.

In fact, his research has found that the more different kinds of media that people use to interact, the stronger their relationships tend to be. People who don’t just talk on the phone but also see each other, and email each other and communicate through four or five different mediums, tend to have stronger relationships with one another than those who communicate through fewer mediums, he has found.

Facebook, he argues, is fundamentally changing the nature of relationships in ways that have been lost since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, when people began leaving their native villages behind to head to cities for new opportunities, and lost contact with the people they grew up with. “Thanks to social media, those types of relationships are persistent,” he says. “Now we may be connecting with people over the course of life that we didn’t before.”

Of course, Facebook and technology, Hampton argues, are not sufficient in their own right to fend off loneliness. But in conjunction with other modes of interaction, they can bolster existing relationships, contribute to diverse relationships, and keep dormant relationships alive. The overall effect of technology is to overcome the constraints of time and location that would have proven insurmountable before. Instead of Christmas cards, we get a constant stream of information. We can share in triumphs and know when to offer solace during tragedy. We are less isolated.

Hampton has heard the assertions by Turkle and others that technology is atomizing us and killing traditional interactions. So he decided to examine that contention too. In a 2014 article in the journalUrban Studies, Hampton and collaborators reported that they had studied four films taken in public spaces over the course of the last 30 years. For their study they observed and coded the behavior and characteristics of 143,593 people. They analyzed that behavior to see if, in fact, we really are “alone together” in a crowd.

In fact, Hampton found the opposite. There was, in the same public spaces, a notable increase in the numbers of people interacting in large groups. And despite the ubiquity of mobile phones, the rate of their use in public was relatively small, especially when individuals were walking with others. Mobile phones appeared “most often in spaces where people might otherwise be walking alone,” he wrote. “This suggests that, when framed as a communication tool, mobile phone use is associated with reduced public isolation, although it is associated with an increased likelihood to linger and with time spent lingering in public.”

None of this surprises Amy Zalman, president and CEO of the World Future Society, who spends her days organizing conferences, conducting research, and speaking with people who try to predict what society might look like a few decades in the future. She expects that technological tools to pursue human relationships will continue to evolve in unexpected ways. But she doesn’t expect them to change human nature. Human relating, she argues, has always been a highly mediated activity—even language can be seen as a tool on the same spectrum as technologies like social media or cell phones, a spectrum of tools we use to interface with others. It’s just that we notice these tools more. But that too will change. “Technology is going to get closer and closer, it’s going to get invasive—we are going to wear it; it’s going to be inside of us—and then it’s going to disappear and we are not even going to notice it,” Zalman says.

Some futurists believe we may plug into a matrix and communicate through a hive mind. Or perhaps we will relate through personal avatars, robots that resemble us, which we occupy remotely. Maybe our brains will be uploaded to computers. But whatever happens, in the end, the verities of happiness will remain the same as they were in the days of Aristotle. It’s never a mistake to go out and play, make friends, make love, and make an impact on society. Happiness is and has always been about our relationships with other people.

Adam Piore is a freelance writer based in New York.