Photo by Guillaume Bourdages on Unsplash

Photo by Guillaume Bourdages on Unsplash

by Dr. Donna Roberts

Source: Going “Back Home” — Looking Back and Moving Forward

THE STORY

I was 40-something. I walked across the threshold of the house I grew up in. It was . . .

From the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man,” to Bon Jovi, who asked, “Who says you can’t go home?” humanity has ruminated on returning to our childhood homes.

The theme is one we revisit repeatedly.

We see it in movies, too, from comedies (The Royal Tenenbaums, Home for the Holidays, This is Where I Leave You) to dramas (On Golden Pond, Young Adult, The Judge) that have poignantly depicted heading home for a visit or a re-nesting. Homecoming is equally well represented in classic and contemporary literature (You Can’t Go Home Again by Thomas Wolfe, Gilead and its sequel Home by Marilynne Robinson, and An American Childhood by Annie Dillard).

Regardless of the circumstances of return — joyous or tragic — the experience is … well … it’s complicated.

For some, home is the ultimate safety net as one walks the tightrope of life — always there, always solid, always ready to catch you should you stumble. For others the concept of home dissipates like a morning dream and there is not much left to go back to, except in one’s head. Some childhood rooms are preserved like a time capsule. Others are transformed into the sewing room Mom always wanted, just days after one’s departure. Millennials are notorious for going back home — provided they left in the first place. This privilege has, supposedly, given them the freedom to pursue their dreams, to fail and fail again, without dire consequences.

So, it is paradise or inferno? As with so much in life, it depends.

To answer Bon Jovi, it was in fact Thomas Wolfe who insisted one cannot go back home again, and yet we have Dorothy returned from Oz proclaiming, “There’s no place like home!”

In the end, good or bad, love it or hate it, curse it or miss it, perhaps Nickleback says it best:

I miss that town

I miss the faces

You can’t erase

You can’t replace it

I miss it now

I can’t believe it

So hard to stay

Too hard to leave itIt’s hard to say it, time to say it

Goodbye … goodbye

PSYCH PSTUFF’S SUMMARY

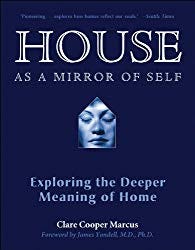

Psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, in his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections, spoke of the home that he built as a “self-realization of the unconscious … a concretization of the individuation process … a symbol of psychic wholeness.” Building on Jung’s work, Clare Cooper Marcus, architect, psychologist and author of House As a Mirror of the Self: Exploring the Deep Meaning of Home, asserts that “as we change and grow throughout our lives, our psychological development is punctuated not only by meaningful emotional relationships with people, but also by close, affective ties with a number of significant physical environments, beginning in childhood.” She insists that, regardless of the external nature of our dwellings — mansions or shacks — we all have a strong emotional relationship, positive or negative, with our homes.

Our census tells us that fewer than 10% of the population remain in the same house they lived in 30 years prior. We are mobile in this 21st century, very mobile. In fact, it is estimated that the average American will move 11.7 times in his or her lifetime. We don’t stay permanently attached to our childhood homes and neighborhoods — at least not physically. But we do, psychologically.

The lure of nostalgia is strong. Millions of adults revisit their childhood homes long after they, or their family members, occupy that space. Some are content to merely drive by and observe from outside. Others write letters to the current owners or even knock on the door and ask to have a look at their old bedroom.

Psychologist Jerry Burger, in his study of the phenomena described in Returning Home: Reconnecting with our Childhoods, noted that approximately one third of American adults over the age of thirty have visited a childhood home — not the people of their childhoods, but the physical locations and structures.

Psychologist Jerry Burger, in his study of the phenomena described in Returning Home: Reconnecting with our Childhoods, noted that approximately one third of American adults over the age of thirty have visited a childhood home — not the people of their childhoods, but the physical locations and structures.We remember, and feel compelled to re-visit, the view from our bedroom window, the schoolyard playground, our dinner table, the front porch and backyard.

Propelled by his own experience of revisiting his childhood haunts, Burger surveyed other adults about their personal pilgrimages “home.” This is some of what he discovered:

There are three primary reasons for making a trip back to one’s childhood home or neighborhood:

• To reconnect with childhood — 42% percent of people Burger interviewed visited their childhood homes in hopes of jogging their memory and getting back in touch with who they were as a child.

• To help resolve a current crisis or problem by reflecting on their past — 15% of those studied expressed the need to reevaluate how they developed their values and what led them to make the decisions that they made.

• To bring closure to unfinished business from childhood — 12% reported abuse or trauma and hoped that returning to the home where they experienced that pain would be therapeutic and cathartic.

Regardless of the underlying motivations for the return, Burger discovered that in almost all of the cases, people reported being glad they made the journey to their childhood home, even though it was often a deeply emotional and unpredictable experience.

He found three exceptions, where the experience was not a positive one and people reported wishing they had not made the trip back to their past:

• When the house in which they grew up had significantly changed or was no longer there — this usually proved unexpected and very upsetting.

• For those who returned anticipating an escape from problems and hoping to relive the romanticized memory of their childhood — in these cases, reality did not match their expectations and they were deeply disappointed and disillusioned.

• For those who returned to work through childhood trauma — often the painful memories seemed more intense while visiting the childhood home and they did not experience the anticipated relief or closure. (Burger recommends people revisiting the past to confront a traumatic period in their lives do so with the help of a professional counselor.)

In any event, there are few experiences in one’s life that can move a person as deeply and unpredictably as returning “home.”

Ω

Photo by

Photo by