Rojas-Berscia and I took a budget flight from Brussels to Malta, arriving at midnight. The air smelled like summer. Our taxi-driver presumed we were mother and son. “How do you say ‘mother’ in Maltese?” Rojas-Berscia asked him, in English. By the time we had reached the hotel, he knew the whole Maltese family. Two local newlyweds, still in their wedding clothes, were just checking in. “How do you say ‘congratulations’?” Rojas-Berscia asked. The answer was nifrah.

We were both starving, so we dropped our bags and went to a local bar. It was Saturday night, and the narrow streets of the quarter were packed with revellers grooving to deafening music. I had pictured something a bit different—a quaint inn on a quiet square, perhaps, where a bronze Knight of Malta tilted at the bougainvillea. But Rojas-Berscia is not easily distracted. He took out his notebook and jotted down the kinship terms he had just learned. Then he checked his phone. “I texted the language guide I lined up for us,” he explained. “He’s a personal trainer I found online, and I’ll start working out with him tomorrow morning. A gym is a good place to get the prepositions for direction.” The trainer arrived and had a beer with us. He was overdressed, with a lacquered mullet, and there was something shifty about him. Indeed, Rojas-Berscia prepaid him for the session, but he never turned up the next day. He had, it transpired, a subsidiary line of work.

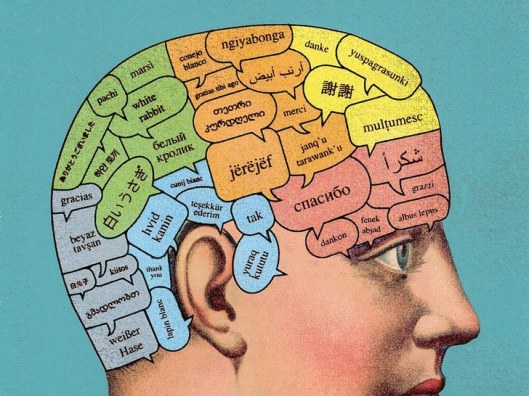

I didn’t expect Rojas-Berscia to master Maltese in a week, but I was surprised at his impromptu approach. He spent several days raptly eavesdropping on native speakers in markets and cafés and on long bus rides, bathing in the warm sea of their voices. If we took a taxi to some church or ruin, he would ride shotgun and ask the driver to teach him a few common Maltese phrases, or to tell him a joke. He didn’t record these encounters, but in the next taxi or shop he would use the new phrases to start a conversation. Hyperpolyglots, Erard writes, exhibit an imperative “will to plasticity,” by which he means plasticity of the brain. But I was seeing plasticity of a different sort, which I myself had once possessed. In my early twenties, I had learned two languages simultaneously, the first by “sleeping with my dictionary,” as the French put it, and the other by drinking a lot of wine and being willing to make a fool of myself jabbering at strangers. With age, I had lost my gift for abandon. That had been my problem with Vietnamese. You have to inhabit a language, not only speak it, and fluency requires some dramatic flair. I should have been hanging out in New York’s Little Saigon, rather than staring at a screen.

The Maltese were flattered by Rojas-Berscia’s interest in their language, but dumbfounded that he would bother to learn it—what use was it to him? Their own history suggests an answer. Malta, an archipelago, is an almost literal stepping stone from Africa to Europe. (While we were there, the government turned away a boatload of asylum seekers.) Its earliest known inhabitants were Neolithic farmers, who were succeeded by the builders of a temple complex on Gozo. (Their mysterious megaliths are still standing.) Around 750 B.C., Phoenician traders established a colony, which was conquered by the Romans, who were routed by the Byzantines, who were kicked out by the Aghlabids. A community of Arabs from the Muslim Emirate of Sicily landed in the eleventh century and dug in so deep that waves of Christian conquest—Norman, Swabian, Aragonese, Spanish, Sicilian, French, and British—couldn’t efface them. Their language is the source of Maltese grammar and a third of the lexicon, making Malti the only Semitic language in the European Union. Rojas-Berscia’s Hebrew helped him with plurals, conjugations, and some roots. As for the rest of the vocabulary, about half comes from Italian, with English and French loanwords. “We should have done Uighur,” I teased him. “This is too easy for you.”

Linguistics gave Rojas-Berscia tools that civilians lack. But he was drawn to linguistics in part because of his aptitude for systematizing. “I can’t remember names,” he told me, yet his recall for the spoken word is preternatural. “It will take me a day to learn the essentials,” he had reckoned, as we planned the trip. The essentials included “predicate formation, how to quantify, negation, pronouns, numbers, qualification—‘good,’ ‘bad,’ and such. Some clausal operators—‘but,’ ‘because,’ ‘therefore.’ Copular verbs like ‘to be’ and ‘to seem.’ Basic survival verbs like ‘need,’ ‘eat,’ ‘see,’ ‘drink,’ ‘want,’ ‘walk,’ ‘buy,’ and ‘get sick.’ Plus a nice little shopping basket of nouns. Then I’ll get our guide to give me a paradigm—‘I eat an apple, you eat an apple’—and voilà.” I had, I realized, covered the same ground in Vietnamese—tôi ăn một quả táo—but it had cost me six months.

It wasn’t easy, though, to find the right guide. I suggested we try the university. “Only if we have to,” Rojas-Berscia said. “I prefer to avoid intellectuals. You want the street talk, not book Maltese.” How would he do this in the Amazon? “Monolingual fieldwork on indigenous tongues, without the reference point of a lingua franca, is harder, but it’s beautiful,” he said. “You start by making bonds with people, learning to greet them appropriately, and observing their gestures. The rules of behavior are at least as important in cultural linguistics as the rules of grammar. It’s not just a matter of finding the algorithm. The goal is to become part of a society.”

After the debacle with the “trainer,” we went looking for volunteers willing to spend an hour or so over a drink or a coffee. We auditioned a tattoo artist with blond dreadlocks, a physiology student from Valletta, a waiter on Gozo, and a tiny old lady who sold tickets to the catacombs outside Mdina (a location for King’s Landing in “Game of Thrones”). Like nearly all Maltese, they spoke good English, though Rojas-Berscia valued their mistakes. “When someone says, ‘He is angry for me,’ you learn something about his language—it represents a convention in Maltese. The richness of a language’s conventions is the highest barrier to sounding like a native in it.”

On our third day, Rojas-Berscia contacted a Maltese Facebook friend, who invited us to dinner in Birgu, a medieval city fortified by the Knights of Malta in the sixteenth century. The sheltered port is now a marina for super-yachts, although a wizened ferryman shuttles humbler travellers from the Birgu quays to those of Senglea, directly across from them. The waterfront is lined with old palazzos of coralline limestone, whose façades were glowing in the dusk. We ordered some Maltese wine and took in the scene. But the minute Rojas-Berscia opened his notebook his attention lasered in on his task. “Please don’t tell me if a verb is regular or not,” he chided his friend, who was being too helpful. “I want my brain to do the work of classifying.”

Rojas-Berscia’s brain is of great interest to Simon Fisher, his senior colleague at the institute and a neurogeneticist of international renown. In 2001, Fisher, then at Oxford, was part of a team that discovered the FOXP2 gene and identified a single, heritable mutation of it that is responsible for verbal dyspraxia, a severe language disorder. In the popular press, FOXP2 has been mistakenly touted as “the language gene,” and as the long-sought evidence for Noam Chomsky’s famous theory, which posits that a spontaneous mutation gave Homo sapiens the ability to acquire speech and that syntax is hard-wired. Other animals, however, including songbirds, also bear a version of the gene, and most of the researchers I met believe that language is probably, as Fisher put it, a “bio-cultural hybrid”—one whose genesis is more complicated than Chomsky would allow. The question inspires bitter controversy.

Fisher’s lab at Nijmegen focusses on pathologies that disrupt speech, but he has started to search for DNA variants that may correlate with linguistic virtuosity. One such quirk has already been discovered, by the neuroscientist Sophie Scott: an extra loop of gray matter, present from birth, in the auditory cortex of some phoneticians. “The genetics of talent is unexplored territory,” Fisher said. “It’s a hard concept to frame for an experiment. It’s also a sensitive topic. But you can’t deny the fact that your genome predisposes you in certain ways.”

The genetics of talent may thwart average linguaphiles who aspire to become Mezzofantis. Transgenerational studies are the next stage of research, and they will seek to establish the degree to which a genius for language runs in the family. Argüelles is the child of a polyglot. Kató Lomb was, too. Simcott’s daughter might contribute to a science still in its infancy. In the meantime, Fisher is recruiting outliers like Rojas-Berscia and collecting their saliva; when the sample is broad enough, he hopes, it will generate some conclusions. “We need to establish the right cutoff point,” he said. “We tend to think it should be twenty languages, rather than the conventional eleven. But there’s a trade-off: with a lower number, we have a bigger cohort.”

I asked Fisher about another cutoff point: the critical period for acquiring a language without an accent. The common wisdom is that one loses the chance to become a spy after puberty. Fisher explained why that is true for most people. A brain, he said, sacrifices suppleness to gain stability as it matures; once you master your mother tongue, you don’t need the phonetic plasticity of childhood, and a typical brain puts that circuitry to another use. But Simcott learned three of the languages in which he is mistaken for a native when he was in his twenties. Corentin Bourdeau, who grew up in the South of France, passes for a local as seamlessly in Lima as he does in Tehran. Experiments in extending or restoring plasticity, in the hope of treating sensory disabilities, may also lead to opportunities for greater acuity. Takao Hensch, at Harvard, has discovered that Valproate, a drug used to treat epilepsy, migraines, and bipolar disorder, can reopen the critical period for visual development in mice. “Might it work for speech?” Fisher said. “We don’t know yet.”

Rojas-Berscia and I parted on the train from Brussels to Nijmegen, where he got off and I continued to the Amsterdam airport. He had to finish his thesis on the Flux Approach before leaving for a research job in Australia, where he planned to study aboriginal languages. I asked him to assess our little experiment. “The grammar was easy,” he said. “The orthography is a little difficult, and the verbs seemed chaotic.” His prowess had dazzled our consultants, but he wasn’t as impressed with himself. He could read bits of a newspaper; he could make small talk; he had learned probably a thousand words. When a taxi-driver asked if he’d been living on Malta for a year, he’d laughed with embarrassment. “I was flattered, of course,” he added. “And his excitement for my progress excited him to help us.” “Excitement about your progress,” I clucked. It was a rare lapse.

A week later, I was on a different train, from New York to Boston. Fisher had referred me to his collaborator Evelina Fedorenko. Fedorenko is a cognitive neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital who also runs what her postdocs call the EvLab, at M.I.T. My first e-mail to her had bounced back—she was on maternity leave. But then she wrote to say that she would be delighted to meet me. “Are you claustrophobic?” she added. If not, she said, I could take a spin in her fMRI machine, to see what she does with her hyperpolyglots.

Fedorenko is small and fair, with delicate features. She was born in Volgograd in 1980. “When the Soviet Union fell apart, we were starving, and it wasn’t fun,” she said. Her father was an alcoholic, but her parents were determined to help her fulfill her exceptional promise in math and science, which meant escaping abroad. At fifteen, she won a place in an exchange program, sponsored by Senator Bill Bradley, and spent a year in Alabama. Harvard gave her a full scholarship in 1998, and she went on to graduate school at M.I.T., in linguistics and psychology. There, she met the cognitive scientist Ted Gibson. They married, and they now have a one-year-old daughter.

One afternoon, I visited Fedorenko at her home, in Belmont. (She spends as much time as she can with her baby, who was babbling like a songbird.) “Here is my basic question,” she said. “How do I get a thought from my mind into yours? We begin by asking how language fits into the broader architecture of the mind. It’s a late invention, evolutionarily, and a lot of the brain’s machinery was already in place.”

She wondered: Does language share a mechanism with other cognitive functions? Or is it autonomous? To seek an answer, she developed a set of “localizer tasks,” administered in an fMRI machine. Her first goal was to identify the “language-responsive cortex,” and the tasks involved reading or listening to a sequence of sentences, some of them garbled or composed of nonsense words.

The responsive cortex proved to be separate from regions involved in other forms of complex thought. We don’t, for example, use the same parts of our brains for music and for speech, which seems counterintuitive, especially in the case of a tonal language. But pitch, Fedorenko explained, has its own neural turf. And life experience alters the picture. “Literate people use one region of their cortex in recognizing letters,” she said. “Illiterate people don’t have that region, though it develops if they learn to read.”

In order to draw general conclusions, Fedorenko needed to study the way that language skills vary among individuals. They turned out to vary greatly. The intensity of activity in response to the localizer tests was idiosyncratic; some brains worked harder than others. But that raised another question: Did heightened activity correspond to a greater aptitude for language? Or was the opposite true—that the cortex of a language prodigy would show less activity, because it was more efficient?

I asked Fedorenko if she had reason to believe that gay, left-handed males on the spectrum had some cerebral advantage in learning languages. “I’m not prepared to accept that reporting as anything more than anecdotal,” she said. “Males, for one thing, get greater encouragement for intellectual achievement.”

Fedorenko’s initial subjects had been English-speaking monolinguals, or bilinguals who also spoke Spanish or Mandarin. But, in 2013, she tested her first prodigy. “We heard about a local kid who spoke thirty languages, and we recruited him,” she said. He introduced her to other whizzes, and as the study grew Fedorenko needed material in a range of tongues. Initially, she used Bible excerpts, but “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” came to seem more congenial. The EvLab has acquired more than forty “Alice” translations, and Fedorenko plans to add tasks in sign language.

Twelve years on, Fedorenko is confident of certain findings. All her subjects show less brain activity when working in their mother tongue; they don’t have to sweat it. As the language in the tests grows more challenging, it elicits more neural activity, until it becomes gibberish, at which point it elicits less—the brain seems to give up, quite sensibly, when a task is futile. Hyperpolyglots, too, work harder in an unfamiliar tongue. But their “harder” is relaxed compared with the efforts of average people. Their advantage seems to be not capacity but efficiency. No matter how difficult the task, they use a smaller area of their brain in processing language—less tissue, less energy.

All Fedorenko’s guinea pigs, including me, also took a daunting nonverbal memory test: squares on a grid flash on and off as you frantically try to recall their location. This trial engages a neural network separate from the language cortex—the executive-function system. “Its role is to support general fluid intelligence,” Fedorenko said. What kind of boost might it give to, say, a language prodigy? “People claim that language learning makes you smarter,” she replied. “Sadly, we don’t have evidence for it. But, if you play an unfamiliar language to ‘normal’ people, their executive-function systems don’t show much response. Those of polyglots do. Perhaps they’re striving to grasp a linguistic signal.” Or perhaps that’s where their genie resides.

Barring an infusion of Valproate, most of us will never acquire Rojas-Berscia’s twenty-eight languages. As for my own brain, I reckoned that the scan would detect a lumpen mass of mac and cheese embedded with low-wattage Christmas lights. After the memory test, I was sure that it had. “Don’t worry,” Matt Siegelman, Fedorenko’s technician, reassured me. “Everyone fails it—well, almost.”

Siegelman’s tactful letdown woke me from my adventures in language land. But as I was leaving I noticed a copy of “Alice” in Vietnamese. I report to you with pride that I could make out “white rabbit” (thỏ trắng), “tea party” (tiệc trà), and ăn tôi, which—you knew it!—means “eat me.” ♦