WRITTEN BY Susan Reynolds Contributor, Psychology Today

Source: What you read matters more than you might think

A study published in the International Journal of Business Administration in May 2016, found that what students read in college directly affects the level of writing they achieve. In fact, researchers found that reading content and frequency may exert more significant impacts on students’ writing ability than writing instruction and writing frequency. Students who read academic journals, literary fiction, or general nonfiction wrote with greater syntactic sophistication (more complex sentences) than those who read fiction (mysteries, fantasy, or science fiction) or exclusively web-based aggregators like Reddit, Tumblr, and BuzzFeed. The highest scores went to those who read academic journals; the lowest scores went to those who relied solely on web-based content.

The difference between deep and light reading

Recent research also revealed that “deep reading”—defined as reading that is slow, immersive, rich in sensory detail and emotional and moral complexity—is distinctive from light reading—little more than the decoding of words. Deep reading occurs when the language is rich in detail, allusion, and metaphor, and taps into the same brain regions that would activate if the reader were experiencing the event. Deep reading is great exercise for the brain, and has been shown to increase empathy, as the reader dives deeper and adds reflection, analysis, and personal subtext to what is being read. It also offers writers a way to appreciate all the qualities that make novels fascinating and meaningful—and to tap into his ability to write on a deeper level.

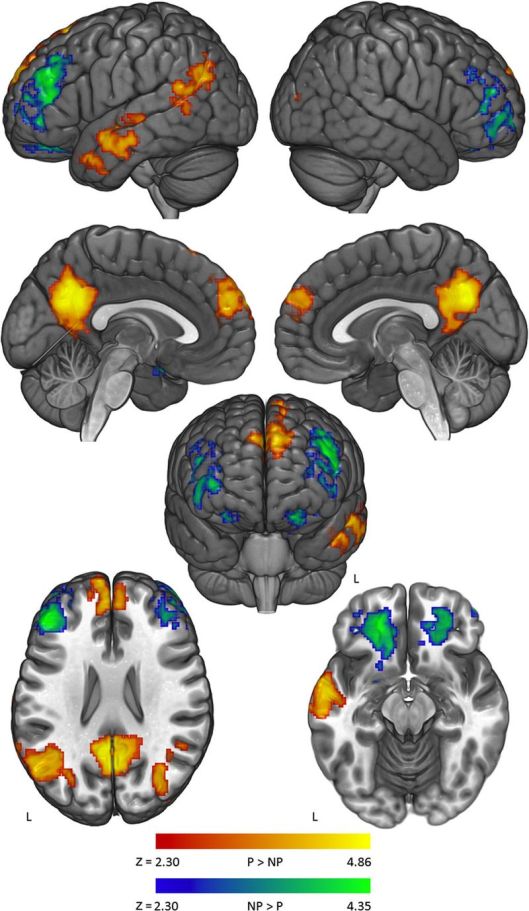

Deep reading synchronizes your brain

Deep reading activates our brain’s centers for speech, vision, and hearing, all of which work together to help us speak, read, and write. Reading and writing engages Broca’s area, which enables us to perceive rhythm and syntax; Wernicke’s area, which impacts our perception of words and meaning; and the angular gyrus, which is central to perception and use of language. These areas are wired together by a band of fibers, and this interconnectivity likely helps writers mimic and synchronize language and rhythms they encounter while reading. Your reading brain senses a cadence that accompanies more complex writing, which your brain then seeks to emulate when writing.

Here are two ways you can use deep reading to fire up your writing brain:

Read poems

In an article published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, researchers reported finding activity in a “reading network” of brain areas that were activated in response to any written material. In addition, more emotionally charged writing aroused several regions in the brain (primarily on the right side) that respond to music. In a specific comparison between reading poetry and prose, researchers found evidence that poetry activates the posterior cingulate cortex and medial temporal lobes, parts of the brain linked to introspection. When volunteers read their favorite poems, areas of the brain associated with memory were stimulated more strongly than “reading areas,” indicating that reading poems you love is the kind of recollection that evokes strong emotions—and strong emotions are always good for creative writing.

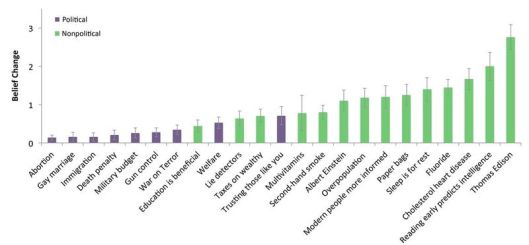

Read literary fiction

Understanding others’ mental states is a crucial skill that enables the complex social relationships that characterize human societies—and that makes a writer excellent at creating multilayered characters and situations. Not much research has been conducted on the theory of mind (our ability to realize that our minds are different than other people’s minds and that their emotions are different from ours) that fosters this skill, but recent experiments revealed that reading literary fiction led to better performance on tests of affective theory of mind (understanding others’ emotions) and cognitive theory of mind (understanding others’ thinking and state of being) compared with reading nonfiction, popular fiction, or nothing at all. Specifically, these results showed that reading literary fiction temporarily enhances theory of mind, and, more broadly, that theory of mind may be influenced greater by engagement with true works of art. In other words, literary fiction provokes thought, contemplation, expansion, and integration. Reading literary fiction stimulates cognition beyond the brain functions related to reading, say, magazine articles, interviews, or most online nonfiction reporting.

Instead of watching TV, focus on deep reading

Time spent watching television is almost always pointless (your brain powers down almost immediately) no matter how hard you try to justify it, and reading fluff magazines or lightweight fiction may be entertaining, but it doesn’t fire up your writing brain. If you’re serious about becoming a better writer, spend lots of time deep-reading literary fiction and poetry and articles on science or art that feature complex language and that require your lovely brain to think.

This post originally appeared at PsychologyToday.com. Susan Reynolds is the author of Fire Up Your Writing Brain, a Writer’s Digest book. You can follow her on Twitter or Facebook.

Jennifer Delgado Suárez

Jennifer Delgado Suárez