We still call them “phones,” but they are seldom used for talking. They have become like a substitute for memory—and other brain functions. Is that good for us in the long run?

Source: Smart Phone, Lazy Brain

You probably know the Google Effect: the first rigorous finding in the booming research into how digital technology affects cognition. It’s also known as digital amnesia, and it works like this: When we know where to find a piece of information, and when it takes little effort to do so, we are less likely to remember that information. First discovered by psychologist Betsy Sparrow of Columbia University and her colleagues, the Google Effect causes our brains to take a pass on retaining or recalling facts such as “an ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain” (an example Sparrow used) when we know they are only a few keystrokes away.

“Because search engines are continually available to us, we may often be in a state of not feeling we need to encode the information internally,” Sparrow explained in her 2011 paper. “When we need it, we will look it up.” Storing information requires mental effort—that’s why we study before exams and cram for presentations—so unless we feel the need to encode something into a memory, we don’t try. Result: Our recollection of ostrich anatomy, and much else, dissipates like foam on a cappuccino.

It’s tempting to leap from the Google Effect to dystopian visions of empty-headed dolts who can’t remember even the route home (thanks a lot, GPS), let alone key events of history (cue Santayana’s hypothesis that those who can’t remember history are doomed to repeat it). But while the short-term effects of digital tech on what we remember and how we think are real, the long-term consequences are unknown; the technology is simply too new for scientists to have figured it out.

People spend an average of 3 to 5 minutes at their computer working on the task at hand before switching to Facebook or other enticing websites.

Before we hit the panic button, it’s worth reminding ourselves that we have been this way before. Plato, for instance, bemoaned the spread of writing, warning that it would decimate people’s ability to remember (why make the effort to encode information in your cortex when you can just consult your handy papyrus?). On the other hand, while writing did not trigger a cognitive apocalypse, scientists are finding more and more evidence that smartphones and internet use are affecting cognition already.

The Google Effect? We’ve probably all experienced it. “Sometimes I spend a few minutes trying hard to remember some fact”—like whether a famous person is alive or dead, or what actor was in a particular movie—“and if I can retrieve it from my memory, it’s there when I try to remember it two, five, seven days later,” said psychologist Larry Rosen, professor emeritus at California State University, Dominguez Hills, who researches the cognitive effects of digital technology. “But if I look it up, I forget it very quickly. If youcan ask your device any question, you do ask your device any question” rather than trying to remember the answer or doing the mental gymnastics to, say, convert Celsius into Fahrenheit.

“Doing that is profoundly impactful,” Rosen said. “It affects your memory as well as your strategy for retrieving memories.” That’s because memories’ physical embodiment in the brain is essentially a long daisy chain of neurons, adding up to something like architectI.M. Pei is alive or swirling water is called an eddy. Whenever we mentally march down that chain we strengthen the synapses connecting one neuron to the next. The very act of retrieving a memory therefore makes it easier to recall next time around. If we succumb to the LMGTFY (let me Google that for you) bait, which has become ridiculously easy with smartphones, that doesn’t happen.

To which the digital native might say, so what? I can still Google whatever I need, whenever I need it. Unfortunately, when facts are no longer accessible to our conscious mind, but only look-up-able, creativity suffers. New ideas come from novel combinations of disparate, seemingly unrelated elements. Just as having many kinds of Legos lets you build more imaginative structures, the more elements—facts—knocking around in your brain the more possible combinations there are, and the more chances for a creative idea or invention. Off-loading more and more knowledge to the internet therefore threatens the very foundations of creativity.

Besides letting us outsource memory, smartphones let us avoid activities that many people find difficult, boring, or even painful: daydreaming, introspecting, thinking through problems. Those are all so aversive, it seems, that nearly half of people in a 2014 experiment whose smartphones were briefly taken away preferred receiving electric shocks than being alone with their thoughts. Yet surely our mental lives are the poorer every time we check Facebook or play Candy Crush instead of daydream.

But why shouldn’t we open the app? The appeal is undeniable. We each have downloaded an average of nearly 30 mobile apps, and spend 87 hours per month internet browsing via smartphone, according to digital marketing company Smart Insights. As a result, distractions are just a click away—and we’re really, really bad at resisting distractions. Our brains evolved to love novelty (maybe human ancestors who were attracted to new environments won the “survival of the fittest” battle), so we flit among different apps and websites.

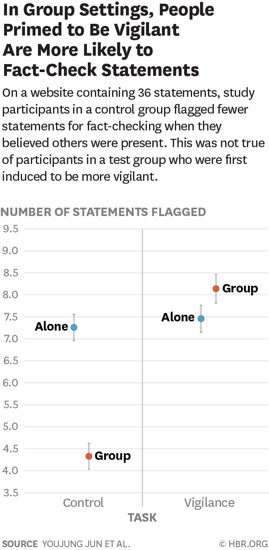

As a result, people spend an average of just three to five minutes at their computer working on the task at hand before switching to Facebook or another enticing website or, with phone beside them, a mobile app. The most pernicious effect of the frenetic, compulsive task switching that smartphones facilitate is to impede the achievement of goals, even small everyday ones. “You can’t reach any complex goal in three minutes,” Rosen said. “There have always been distractions, but while giving in used to require effort, like getting up and making a sandwich, now the distraction is right there on your screen.”

The mere existence of distractions is harmful because resisting distractions that we see out of the corner of our eye (that Twitter app sitting right there on our iPhone screen) takes effort. Using fMRI to measure brain activity, neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley of the University of California, San Francisco, found that when people try to ignore distractions it requires significant mental resources. Signals from the prefrontal cortex race down to the visual cortex, suppressing neuronal activity and thereby filtering out what the brain’s higher-order cognitive regions have deemed irrelevant. So far, so good.

The problem is that the same prefrontal regions are also required for judgment, attention, problem solving, weighing options, and working memory, all of which are required to accomplish a goal. Our brains have limited capacity to do all that. If the prefrontal cortex is mightily resisting distractions, it isn’t hunkering down to finish the term paper, monthly progress report, sales projections, or other goal it’s supposed to be working toward. “We are all cruising along on a superhighway of interference” produced by the ubiquity of digital technology, Gazzaley and Rosen wrote in their 2016 book The Distracted Mind. That impedes our ability to accomplish everyday goals, to say nothing of the grander ones that are built on the smaller ones.

The constant competition for our attention from all the goodies on our phone and other screens means that we engage in what a Microsoft scientist called “continuous partial attention.” We just don’t get our minds deeply into any one task or topic. Will that have consequences for how intelligent, creative, clever, and thoughtful we are? “It’s too soon to know,” Rosen said, “but there is a big experiment going on, and we are the lab rats.”

Tech Invasion LMGTFY

“Let me Google that for you” may be some of the most damaging words for our brain. Psychologists have theorized that the “Google Effect” causes our memories to weaken due merely to the fact that we know we can look something up, which means we don’t keep pounding away at the pathways that strengthen memory. Meanwhile, research suggests that relying on GPS weakens our age-old ability to navigate our surroundings. And to top it all off, the access to novel info popping up on our phone means that, according to Deloitte, people in the US check their phones an average of 46 times per day—which is more than a little disruptive.

Illustration by Edmon Haro

Illustration by Edmon Haro

Most parents have an idea when their child’s screen-time has become problematic. However, new research has given us astandardized way to determine if those hours of screen-time are problematic. A group of researchers have created the

Most parents have an idea when their child’s screen-time has become problematic. However, new research has given us astandardized way to determine if those hours of screen-time are problematic. A group of researchers have created the